Jack O’Neill, Santa Cruz surf wetsuit pioneer, dies

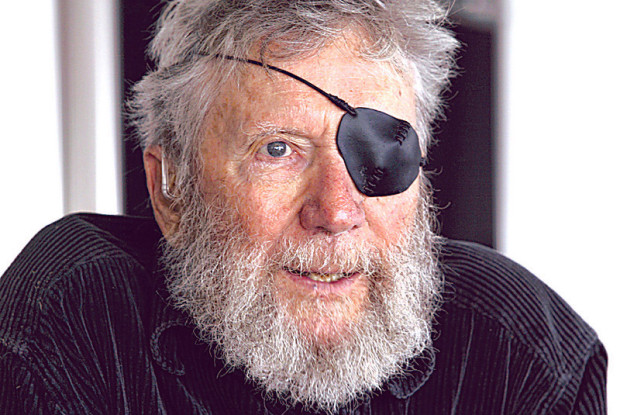

SANTA CRUZ, Calif. —Jack O’Neill, the eye patch wearing wetsuit pioneer who trail-blazed cold water surfing, has died, friends confirmed to KSBW Friday.

He was 94.

O’Neill single-handedly opened up the possibility of surfing Northern and Central California’s cold water year-round with his industry-changing wetsuits.

He lived out his days in his legendary moss-green house perched over the ocean along East Cliff Drive in Santa Cruz. Surfers affectionately refer to the surf spot where perfect waves roll up to O’Neill’s steps as “Jack’s.”

He passed away peacefully at home with his family by his side.

“It’s a sad day for surfing,” Mavericks big wave surfer Ken “Skindog” Collins said Friday.

“It’s sad news. You drive by Pleasure Point, and you see that house every time, and you get a little reflection of how much surfing means to this community. And what he brought to this community,” big wave surfer Peter Mel said.

VIDEO: Jack O’Neill reflects on his life

Sixty-five years ago, O’Neill set up a small surf shop at Ocean Beach in San Francisco and revealed his neoprene prototype. He moved to Santa Cruz in 1959, during a time when the surfing scene was nothing like it is today, and set up another surf shop at Cowell Beach.

“Guys were using sweaters from the Goodwill. I remember one guy got a jumper from the Goodwill and sprayed it with Thompson’s water seal, and he set out there in an oil slick,” O’Neill said in a 1999 interview.

Surfers who braved frigid ocean water without wetsuits couldn’t last for very long sesh’s.

While O’Neill’s early wetsuits were eyed with skepticism, he continued experimenting with neoprene, a material that is still used today.

His iconic pirate-like black eye patch was the result of a surfing accident when he fell while riding a wave at the Hook.

He lived for surfing and being close to nature.

“I remember going to sleep at night. You see that wave, that wall of water, and that tube. It’s something with being close to nature like that, pretty hard to beat,” O’Neill said.

O’Neill said he always considered Santa Cruz as “the center of surfing,” outside Southern California’s warmer waters. In 1964 he created the O’Neill surf team, giving up-and-coming young surfers new surfboards.

So far, there’s no official word on O’Neill’s cause of death.

–The following article below was printed in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2012:

Jack O’Neill, a surfing legend who endures

As surf houses go, Jack O’Neill’s is pretty legendary. Perched conspicuously on a cliff overlooking Monterey Bay, it’s the only building occupying the half-mile of eroding sandstone bluffs that run along Santa Cruz’s east side. Inside, the walls are covered with black-and- white photos of hot air balloons and unconventional seacraft. Telescopes compete with blueprints for floor space. Long ago, the main stairwell was cleared to make room for a trampoline. The bottom floor boasts a submarine steel door in place of a wooden one.

“This is my pad,” the 89-year-old O’Neill, founder of the O’Neill surf brand, says proudly as he gazes through the panoramic window at the waves and surfers below. While it may seem like an obvious point these days, every surfer is wearing a wetsuit.

It wasn’t always so. Sixty years ago, O’Neill introduced a prototype of a wetsuit and opened one of the world’s first surf shops along Ocean Beach in San Francisco. In the intervening years, the wetsuit has helped spread surfing from the balmy waters of Polynesia and Southern California to nearly every ocean-bearing corner of the world. As the sport evolved from a hobby popular among layabouts and eccentrics into a global industry, O’Neill became its primary spokesman – and one of its most enduring legends.

Yet while his innovations, business acumen, and adventurer’s pedigree have made him an international figure in the surfing world, he seems most content being home close to his beloved Pacific.

“I’m not much into business, I’m into the ocean,” he says as he hoists his sandal-clad feet onto an ottoman.

Settling in San Francisco after a stint as a pilot in the Naval Air Corps in the ’40s, O’Neill joined a small crew of men who bodysurfed the bitterly cold waters off Ocean Beach, a pastime that he says provided relief from a claustrophobic job downtown that would get him “all screwed up” with unspent energy. With water temperatures in the low 50s year-round, he and his friends used wool jerseys, bonfires, even liquor to stay warm.Turns as a taxi driver, fisherman, lifeguard, longshoreman, traveling salesman and draftsman left him still searching for a niche. He found his mark when a friend and UC School of Pharmacy (now UCSF) grad Harry Hind suggested that neoprene rubber would be a great insulator against the cold.

At the time, a UC Berkeley engineer and others were tinkering with neoprene as an insulator for deep-sea diving. Much in the way Steve Jobs appropriated the computer mouse from Xerox, O’Neill found a way to translate the emerging technology into a product people would clamor for.

In 1952, within months of introducing his experimental vests, he opened the surf shop in a garage off the Great Highway (he trademarked the term “surf shop” in 1962, but never enforced it).

His engineer’s eye created the most coveted designs on the market. By the time the wetsuit became a must-have for an exploding population of surfers, O’Neill was poised for a windfall. Within the decade he’d upgrade to a bigger space in Santa Cruz. Within two decades, the O’Neill brand would be one of the most recognizable surfing emblems in the world. No longer impeded by geography or season, surfing would eventually become a $6-billion-a-year industry.

But when he moved to Santa Cruz in 1959, the town was an isolated, rural outpost. It was so wild that the O’Neill family had a pet seal that would clamber up to their doorstep for food.

“I definitely stood out,” O’Neill says. “At the time surfers were thought of as a bunch of bums. I had a surfer friend who wanted to work for the police and when he went to the station the chief took one look at the surfboard on his car and said, ‘Policemen don’t surf.'”

O’Neill gradually changed that perception.

“Jack decided he had to become a standup member of the community,” says his son Pat, who has been the company’s CEO and president for 25 years. “He’s always got along really well with people from all walks of life. As a result, he became friends with people from all over the social and political spectrum. He had friends that were wealthy and powerful in Santa Cruz and people who lived in cars.”

Although O’Neill is mainly associated with surfing, he was an adventurer in other ways. An accomplished sailor and aviator, he was among the first to fly hot air balloons recreationally, and he invented the sand sailor, a sailboat on wheels that skirts along the sand.

Often he’d use personal quirks to help promote his business. In 1972, he lost an eye surfing off Santa Cruz, forcing him to wear a patch. The patch has since become something of a trademark, forever associated with the O’Neill brand.

“Of all the things Jack is known for, I think his genius for marketing and promoting stood out,” says surfing historian Matt Warshaw. “In the very first issue of Surfer (magazine), O’Neill had the best logo. He used to drop into surf contests in his bright yellow hot air balloon. He even managed to turn this horrible adversity – losing an eye – into a great marketing thing.” (For the record, O’Neill says losing an eye didn’t change the way he goes about his life. “I didn’t think much about it, really.”)

As the cult of his personality grew, so did his businesses. Besides selling wetsuits, he was one of the first to blow foam for surfboards instead of using balsa wood. He opened an 8,400-square-foot yacht center in Santa Cruz harbor and even helped salvage sunken ships. Meanwhile, he and wife Marjorie raised six children before she died in 1973.

Drew Kampion, who has known O’Neill for more than 40 years and recently published a biography of him, says, “His life was just integrated. He brought together all these vectors – his family, his passion for the ocean, for business, his autodidactic side – into this well of self-sustaining energy. He’s just uncompromising when it comes to what he loves.”Today O’Neill’s business employs 130 people in the United States, and Logo International, the Dutch company that purchased the trademark in 2007, has licensing agreements to sell apparel and a line of snow gear around the world. The Santa Cruz wetsuit enterprise retains a leading market share – an estimated 60 percent – of international wetsuit sales.

Since assuming a reduced role in the company after having a stroke in 2005, O’Neill has pursued projects like the O’Neill Sea Odyssey program, using his 65-foot research catamaran to take kids out on Monterey Bay and teach them about ocean preservation.

He has also helped foster recognition for his beloved Santa Cruz, which recently was named a World Surfing Reserve, one of only four spots in the world so designated. While it carries no legal weight, being named a reserve helps guard the city’s 23 surf spots against threats from pollution and coastal development.

As he is prone to do, O’Neill turns philosophical when asked about the sea and what he calls the “healing powers” of the ocean.

“I’ve felt this in my own life, but there are also researchers interested in studying the way ocean therapy affects the brain and its pathways,” he says. “It’s proved therapeutic for people with physical and mental disabilities, for veterans returning from war, for everyone. I think in the next 30 years we’ll see the potential of that power become fully realized.”

It’s that kind of foresight that has made him a hero to ocean-minded people like 68-year-old Santa Cruz surf star Jim Phillips. Phillips was just a kid when O’Neill hired him to glass surfboards in his shop.

“You’re often disappointed by your idols,” Phillips says. “But, you know, I never have been with Jack.”

Source: KSBW8