SURFER FIRST AID: HOW TO SURVIVE A SHARK ATTACK

AND TWO OTHER SCENARIOS

Posted August 10, 2017

A few months ago I had the horrible experience of being in the water when my friend broke his neck and nearly drowned in Namibia.

His life was saved by the lightning fast reaction of a fellow surfer, who brought him safely to shore. I was called out the water due to the fact I am a doctor, and after a quick assessment I did nothing more than keep him company while we waited for an ambulance.

While I was sat there next to him I got to thinking about the different emergencies one could face whilst surfing, and how to approach them. I came to the realisation that on the beach, with none of the usual equipment and support of a hospital, only the very basic aspects of emergency medicine can be performed, and these basic things can save someone’s life. I also realised that none of these things need a medical degree, or any medical experience whatsoever, to perform well.

Every surfer should have an idea in their head of what to do should the worst happen, and with that in mind I am going to discuss the initial management of three different life-threatening situations that one could encounter whilst surfing: a conscious person with a possible neck injury, an unresponsive person and a shark attack victim.

The first thing to consider in any emergency is the safety of the rescuer(s). Every situation will be different, and your willingness to put yourself in danger will depend on a multitude of factors; the severity of the danger, your competence and fitness, your relationship to the injured person etc. The decision to put yourself at risk or not will have to be taken in the moment, and everyone will react differently, but always try to remain calm, assess the situation, call for help early and avoid taking unnecessary risks. The worst thing you can do is turn one casualty into two.

Scenario 1 – Conscious patient, suspected neck injury

You are surfing your local thumping bebeach breakhen you see someone go over the falls. It looks heavy, and you see that when he surfaces he is not moving properly and looks to be in trouble. You quickly paddle over and he says that his neck hurts and he can’t feel his legs.

In this situation the biggest threat to the patient is drowning in the surf and further damage to the spinal cord due to excess movement. Try and recruit as many helpers as possible, and if in deep water use available flotation devices (surfboard) for assistance. Your priorities are to get them safely to the shore, whilst minimising movement of the spine by providing manual in-line stabilisation (keeping their whole spine as straight as possible).

There are a number of ways to achieve this, the choice of which will depend on your experience and the depth of water/distance from shore. A simple and effective way to retrieve someone from shallow water alone is by placing the injured person’s arms above their head and holding them there with one hand to form a splint, and using your free hand and legs to swim on your back or wade to shore.

Always move backwards, facing out to sea, so that you and the victim can be ready to brace when a wave hits. Once on the shore check that the person is responsive, place them flat on their back, instruct them not to move their head and have someone manually brace their head until the ambulance arrives.

DO:

Call for help early, get as many people to help as possible.

Try to minimise movement of the spine throughout the rescue.

Reassure the person and keep them warm.

DON’T:

Put the injured person in the recovery position.

Give them any food or drink.

Scenario 2 – Unresponsive person, suspected drowning

You are surfing a heavy break when fellow surfers start shouting and pointing to someone lying face down in the impact zone. You paddle over and the person is unresponsive.

In this situation the biggest threat to the person is death due to drowning. There is also the possibility of a spinal injury if in shallow surf. The first and most important treatment of the drowning person is the rapid provision of ventilation (air to the lungs). Prompt initiation of rescue breathing increases the person’s chance of survival. Your priority is to get the person quickly to shore, assess for signs of life, and if none are present to commence good quality CPR starting with 5 rescue breaths

Time is critical, and whilst care should be taken to avoid unnecessary movement of the spine, this should not delay a rapid retrieval. Once the patient is on the shore, lie them flat on their back on a firm surface and spend no longer than ten seconds assessing for signs of life. If they are unresponsive and are not breathing, or breathing abnormally, call for help and immediately begin CPR.

DO:

Get the person quickly to shore

Assess briefly for signs of life, and if none are present, commence CPR starting with five rescue breaths

Rotate CPR providers to prevent fatigue and ensure good quality is maintained

Turn person on their side briefly if vomiting occurs

Attend a course on Basic Life Support or at the very least watch the attached tutorial

DON’T:

Try and administer rescue breaths in the water unless you are trained to do so and expect a significant delay in getting to shore

Spend more than ten seconds looking for signs of life – if in doubt, start CPR

Stop CPR until signs of life return or the paramedics take over

Scenario three – Shark attack

The nightmare scenario; you are surfing when a fellow surfer starts screaming and it becomes obvious that they have been attacked by a shark, with significant blood loss visible.

In this situation the biggest threat to the victim is death due to blood loss. An athletic adult will be able to compensate up to the loss of around two litres of blood, after which they will rapidly decompensate and death will follow shortly after unless the bleeding is stopped and the blood replaced.

If an artery is severed this process can happen within minutes. The key priority here is to stop the bleeding as soon as possible and get the patient to a hospital urgently. Call for help and get the patient out the water, position them with their head to water on a sloped beach and/or elevate any uninjured leg(s) to maximise blood flow to the brain, then apply firm direct pressure to the wound using a towel or item of clothing. If the victim is wearing a wetsuit, cut this off to allow assessment of the wound and direct pressure. Try and keep the patient as warm as possible, as hypothermia worsens any bleeding.

If the wound is on a leg or an arm and direct pressure is insufficient to stop the bleeding, it might be necessary to use a tourniquet. The use of tourniquets is well proven in military settings and the evidence is increasingly in favour of their use in civilian settings, including makeshift tourniquets.

There is a risk of causing damage to the limb so only use them when the benefits of preventing death from massive blood loss outweigh the risk of causing damage to the limb. For a tourniquet to be effective, a windlass should be used (some form of solid lever used to wind the tourniquet tight).

Cut/tear a strip of cloth 5-10cm wide and tie it loosely in a half granny knot just above the wound, avoiding joints. Place a stick/pen/item of cutlery over the knot and complete the tie. Rotate the stick as a windlass, tightening the tourniquet until the bleeding stops. Record the time the tourniquet was applied, and convey this to the paramedics. Using my obliging brother I tested a number of materials for a makeshift tourniquet, and was able to successfully stop arterial blood flow in both the arm and leg using a sock/ surfboard leash/strip of cloth with a pen or a fork for a windlass.

DO:

Get the victim to shore as quickly as possible.

Immediately call for emergency services, and inform the operator that it has been a shark attack with suspected significant blood loss.

Keep the patient warm.

Apply firm direct pressure to the wound.

If this fails and the wound is on a limb, fashion a tourniquet.

Start CPR if the patient becomes unresponsive and there are no signs of life.

DON’T:

Worry about spinal injuries, it is highly unlikely.

How to perform CPR

Submersion durations of less than 10 mins are associated with a very good chance of a positive outcome, if good quality CPR is provided. However, providing good quality CPR is a skill, and it is highly advisable for everyone to attend a Basic Life Support course to learn it.

These can often be done through your employers or local providers. Watching the attached YouTube tutorial is a good start. The key things to remember in this situation are: start with five rescue breaths, followed by chest compressions and rescue breaths at a ratio of 30 compressions to two breaths, chest compressions should be performed with both hands over the sternum (between the nipples) at a rate of around 100 beats per minute, to a depth of around 6cm in adults, for effective rescue breaths the nose should be pinched and a tight seal made around the mouth, watching the chest for rising when the breath is administered.

If possible always try and rotate CPR providers every two minutes to prevent fatigue and ensure good quality compressions. If an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) is available (for example lifeguard station or beachfront hotel) this should be used. Once CPR is started it should not be stopped until the patient recovers signs of life or the paramedics take over.

The above information is intended as basic advice for the layperson with no first aid experience. I highly recommend that every surfer should attend a Basic Life Support course which will provide invaluable practical experience.

While the utmost care has been taken to ensure that all the advice presented is accurate and up to date, guidelines may vary from country to country. For the purposes of this article I have used the most recent UK Resuscitation Council guidelines (2015), the most recent American Heart Association ‘Cardiac arrest in special situations’ guidelines (2010) and the Oxford handbook of expedition and wilderness medicine, 2nd Edition (2015)

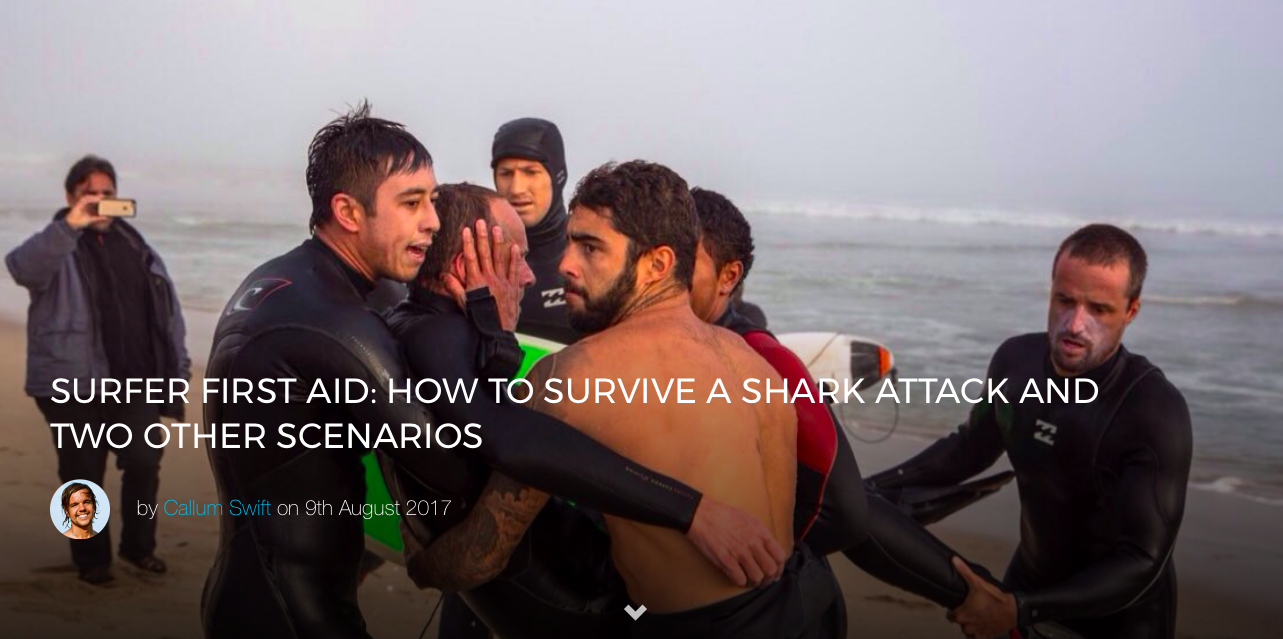

Cover shot: Eli Olsen providing manual in-line stabalisation of the spine during a rescue by Alan Van Gysen

(c) Towsurfer.com 2017